Photo Credit: Angie Gottschalk, Ithaca Journal

Thirty years ago, before a sparse audience scattered throughout a cavernous auditorium at Cornell University, a petite woman argued passionately about the meaning of the U.S. Constitution. As her fellow symposium panelists — Cornell professors of law, government, and history — debated the technicalities of the document, she pushed for broader questions to be asked on issues that the Constitution is silent on, including “affirmative rights” and “cultural and social guarantees.” ‘’ ‘Our Constitution is defective in that respect’ she said. ‘Why should the U.S. Constitution be a model for the world? Who needs freedom of speech when you have an empty belly?’ ” (Yaukey, Ithaca Journal, September 19, 1987, p. 4A)

Much has changed in the intervening years. That appellate judge and pioneering women’s rights advocate who couldn’t draw a decent-sized crowd at her own alma mater, is now a pop culture icon. Journalists breathlessly report on her fashion sensibilities (fishnet gloves anyone?) or when she is spotted carrying a tote bag with her own face on it. Kids dress up as her for Halloween and adore her coloring book.

Much has changed in the intervening years. That appellate judge and pioneering women’s rights advocate who couldn’t draw a decent-sized crowd at her own alma mater, is now a pop culture icon. Journalists breathlessly report on her fashion sensibilities (fishnet gloves anyone?) or when she is spotted carrying a tote bag with her own face on it. Kids dress up as her for Halloween and adore her coloring book.

One thing hasn’t changed though: Ruth Bader Ginsburg still has plenty to say about the Constitution.

A lot has also been said and written about Justice Ginsburg, who holds an honorary degree from BLS. The following are some relevant titles in the BLS Library collection to consider putting on your summer reading list:

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg by Irin Carmon & Shana Knizhnik (2015). [Call number: KF8745.G56 C37 2015] The elevation of RBG to her current status as a cultural icon can be traced to the Notorious R.B.G. Tumblr created by Shana Knizhnik, one of the book’s co-authors, in 2013. This title is a colorful and entertaining look at Ginsburg’s life and career. We get plenty of juicy nuggets about her Brooklyn childhood and nickname (Kiki), her favorite bathroom at Cornell where she could get schoolwork done (in the architecture school), the time she couldn’t check a citation as a Harvard Law Review member (the volume was located in a men-only library reading room), and how her mentor Prof. Gerald Gunther had to “blackmail” federal judge Edmund Palmieri so she could secure a clerkship (Justice Frankfurter flatly said no; Judge Learned Hand refused to hire women as he was “potty-mouthed” and did not want to watch his language around women.) Notorious RBG remains accessible even when it starts covering the denser legal material from Ginsburg’s time as a law professor, at the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, and her judicial tenure. Excerpts from the brief she authored in Reed v. Reed (1971), her majority opinion in the VMI gender discrimination case, United States v. Virginia (1996), and the dissent she read from the bench in the equal pay case Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. (2007) (that helped spur passage of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009) are all meticulously annotated so as to be readily understood by the layperson. RBG’s loving marriage to Marty Ginsburg shines through: the last note he wrote to her before he died from cancer, reproduced in the original, is especially touching. Even if you don’t want to read all the material, skimming through the many photographs and illustrations in the volume can be a joy.

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg by Irin Carmon & Shana Knizhnik (2015). [Call number: KF8745.G56 C37 2015] The elevation of RBG to her current status as a cultural icon can be traced to the Notorious R.B.G. Tumblr created by Shana Knizhnik, one of the book’s co-authors, in 2013. This title is a colorful and entertaining look at Ginsburg’s life and career. We get plenty of juicy nuggets about her Brooklyn childhood and nickname (Kiki), her favorite bathroom at Cornell where she could get schoolwork done (in the architecture school), the time she couldn’t check a citation as a Harvard Law Review member (the volume was located in a men-only library reading room), and how her mentor Prof. Gerald Gunther had to “blackmail” federal judge Edmund Palmieri so she could secure a clerkship (Justice Frankfurter flatly said no; Judge Learned Hand refused to hire women as he was “potty-mouthed” and did not want to watch his language around women.) Notorious RBG remains accessible even when it starts covering the denser legal material from Ginsburg’s time as a law professor, at the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, and her judicial tenure. Excerpts from the brief she authored in Reed v. Reed (1971), her majority opinion in the VMI gender discrimination case, United States v. Virginia (1996), and the dissent she read from the bench in the equal pay case Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. (2007) (that helped spur passage of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009) are all meticulously annotated so as to be readily understood by the layperson. RBG’s loving marriage to Marty Ginsburg shines through: the last note he wrote to her before he died from cancer, reproduced in the original, is especially touching. Even if you don’t want to read all the material, skimming through the many photographs and illustrations in the volume can be a joy.

My Own Words by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with Mary Hartnett and Wendy W. Williams (2016) [Call number: KF373.G565 G56 2016] My Own Words is a collection of Ginsburg’s writings and speeches which are given context by short introductory essays by her co-authors. Especially interesting are the early documents: a school newspaper editorial from June 1946 that champions the new United Nations Charter; “One People”, a 1946 article for the East Midwood Jewish Center Bulletin (religious school graduation issue) discussing post-war unity; and a 1953 letter to the editor published in the Cornell Daily Sun titled “Wiretapping: Cure worse than Disease?” We get some insight into Ginsburg’s love for opera, friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia, and why her given name Joan never stuck. Her family and marriage get some attention: husband Marty was a true partner, did all the cooking, and was the biggest champion of his wife — decades after the fact, he remained annoyed at Harvard Law School for not allowing RBG to be awarded a Harvard degree after completing her third year at Columbia. Yet My Own Words feels incomplete: despite the many speeches, law review articles, briefs, and judicial opinions contained in the volume, Ginsburg’s personality and character remain elusive. This is a function of the limited scope of the project: RBG’s co-authors Mary Hartnett and Wendy Williams are her official biographers, and one gets the sense that more personally revealing anecdotes and materials are being held back for the main publication that will follow.

My Own Words by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with Mary Hartnett and Wendy W. Williams (2016) [Call number: KF373.G565 G56 2016] My Own Words is a collection of Ginsburg’s writings and speeches which are given context by short introductory essays by her co-authors. Especially interesting are the early documents: a school newspaper editorial from June 1946 that champions the new United Nations Charter; “One People”, a 1946 article for the East Midwood Jewish Center Bulletin (religious school graduation issue) discussing post-war unity; and a 1953 letter to the editor published in the Cornell Daily Sun titled “Wiretapping: Cure worse than Disease?” We get some insight into Ginsburg’s love for opera, friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia, and why her given name Joan never stuck. Her family and marriage get some attention: husband Marty was a true partner, did all the cooking, and was the biggest champion of his wife — decades after the fact, he remained annoyed at Harvard Law School for not allowing RBG to be awarded a Harvard degree after completing her third year at Columbia. Yet My Own Words feels incomplete: despite the many speeches, law review articles, briefs, and judicial opinions contained in the volume, Ginsburg’s personality and character remain elusive. This is a function of the limited scope of the project: RBG’s co-authors Mary Hartnett and Wendy Williams are her official biographers, and one gets the sense that more personally revealing anecdotes and materials are being held back for the main publication that will follow.

Brief for Appellant, Reed v. Reed

The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg by Scott Dodson (ed.) (2015) [Call number: KF8745.G56 L4499 2015] This volume is a collection of 16 essays from legal luminaries that include Herma Hill Kay, Nina Totenberg, Lani Guinier, Tom Goldstein, and many more. Linda Kerber’s essay “Before Frontiero there was Reed” vividly traces the history of Reed v. Reed, the first case in which the Supreme Court held that arbitrary discrimination based on gender violated the Equal Protection clause. As Kerber writes, Ginsburg added the names of Pauli Murray and Dorothy Kenyon to her Reed brief; even though neither had written a word, RBG “understood more clearly than anyone of her time the debt that the women of her generation [ ] owed to those of preceding generations.” Many of the essays focus on doctrine — criminal procedure, jurisdiction, federalism — but the closing essays speak to her temperament and approach to life and the law. The closing essay “Fire and Ice: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Least Likely Firebrand” by Dahlia Lithwick is especially revealing. Lithwick describes how Ginsburg’s judicial voice grew exponentially after Justice O’Connor retired and RBG was left the only woman on the court. Faced with the male Justices’ insensitivities during oral argument in Safford Unified School District v. Redding (2009), a case in which school officials strip searched a teenaged female student, RBG took the unprecedented step of granting an interview while the decision was still pending. In the interview, Ginsburg told Joan Biskupic of USA Today (who was also Justice O’Connor’s biographer) that her colleagues “have never been a 13-year-old girl” and that more women were needed on the court. The student prevailed 8-1 in her claim against the school district. And perhaps it was no coincidence that just 3 weeks after the USA Today interview was published, President Obama nominated Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court.

Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg went to the Supreme Court and changed the world by Linda Hirshman (2015). [Call number: KF8744 .H57 2015] Sisters in Law traces the background of two ostensibly very different women, one a Goldwater Girl, the other a card-carrying member of the ACLU, who ended up as pioneers on the Supreme Court. Justice O’Connor was known to be a centrist, a “justice-as-legislator” who believed in “playing defense” to protect hard-earned gains and who adhered to incrementalism. In contrast, Ginsburg with her litigation and advocacy background was used to “playing offense.” Nevertheless, once RBG reached the court, she quickly determined that of all the relationships she needed to develop, the most important was the one with O’Connor. Justice O’Connor, who had over the years been fed many of RBG’s clerks, reciprocated. Contrary to tradition, RBG’s first assigned majority opinion for the court was not a unanimous decision but rather a complex ERISA case on which the Justices had split 6-3. After Ginsburg had successfully navigated her way through this first challenge, O’Connor, who had dissented, sent her a note that read: “This is your first opinion for the Court, it is a fine one, I look forward to many more.” Hirshman also includes an anecdote about how RBG, as the first Jewish justice in a generation, helped change court practices. Upon joining the court, Ginsburg sent a letter to Chief Justice Rehnquist, siding with Orthodox Jewish lawyers who objected to the year on their certificates of admission being worded as “The Year of Our Lord.” She encountered resistance from an unnamed colleague (the author suspects Rehnquist or Blackmun) “Why are you making a fuss about this? It was good enough for Brandeis, it was good enough for Cardozo and Frankfurter.” RBG’s response? “It’s not good enough for Ginsburg.” The Court ultimately acquiesced. There is plenty in this book to chew on about both the differences and shared experiences of the first two female Supreme Court Justices, and how they have changed the dynamic of the Court forever.

Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg went to the Supreme Court and changed the world by Linda Hirshman (2015). [Call number: KF8744 .H57 2015] Sisters in Law traces the background of two ostensibly very different women, one a Goldwater Girl, the other a card-carrying member of the ACLU, who ended up as pioneers on the Supreme Court. Justice O’Connor was known to be a centrist, a “justice-as-legislator” who believed in “playing defense” to protect hard-earned gains and who adhered to incrementalism. In contrast, Ginsburg with her litigation and advocacy background was used to “playing offense.” Nevertheless, once RBG reached the court, she quickly determined that of all the relationships she needed to develop, the most important was the one with O’Connor. Justice O’Connor, who had over the years been fed many of RBG’s clerks, reciprocated. Contrary to tradition, RBG’s first assigned majority opinion for the court was not a unanimous decision but rather a complex ERISA case on which the Justices had split 6-3. After Ginsburg had successfully navigated her way through this first challenge, O’Connor, who had dissented, sent her a note that read: “This is your first opinion for the Court, it is a fine one, I look forward to many more.” Hirshman also includes an anecdote about how RBG, as the first Jewish justice in a generation, helped change court practices. Upon joining the court, Ginsburg sent a letter to Chief Justice Rehnquist, siding with Orthodox Jewish lawyers who objected to the year on their certificates of admission being worded as “The Year of Our Lord.” She encountered resistance from an unnamed colleague (the author suspects Rehnquist or Blackmun) “Why are you making a fuss about this? It was good enough for Brandeis, it was good enough for Cardozo and Frankfurter.” RBG’s response? “It’s not good enough for Ginsburg.” The Court ultimately acquiesced. There is plenty in this book to chew on about both the differences and shared experiences of the first two female Supreme Court Justices, and how they have changed the dynamic of the Court forever.

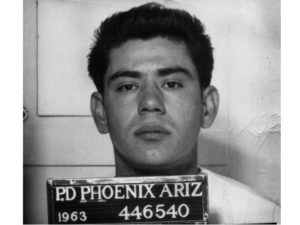

The Brooklyn Law School Library has in its collection The Constitutional Rights of Children: In re Gault and Juvenile Justice by David S. Tanenhaus (Call No. KF228.G377 T36 2017). This new edition includes expanded coverage of the Roberts Court’s juvenile justice decisions including Miller v. Alabama (in which the Court held that mandatory sentences of life without the possibility of parole are unconstitutional for juvenile offenders) and explains how disregard for children’s constitutional rights led to the “Kids for Cash” scandal in Pennsylvania. Widely celebrated as the most important children’s rights case of the twentieth century, Gault affirmed that children have the same rights as adults and formally incorporated the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process protections into the administration of the nation’s juvenile courts.

The Brooklyn Law School Library has in its collection The Constitutional Rights of Children: In re Gault and Juvenile Justice by David S. Tanenhaus (Call No. KF228.G377 T36 2017). This new edition includes expanded coverage of the Roberts Court’s juvenile justice decisions including Miller v. Alabama (in which the Court held that mandatory sentences of life without the possibility of parole are unconstitutional for juvenile offenders) and explains how disregard for children’s constitutional rights led to the “Kids for Cash” scandal in Pennsylvania. Widely celebrated as the most important children’s rights case of the twentieth century, Gault affirmed that children have the same rights as adults and formally incorporated the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process protections into the administration of the nation’s juvenile courts.

The Unexpected Scalia: A Conservative Justice’s Liberal Opinions

The Unexpected Scalia: A Conservative Justice’s Liberal Opinions

Chair of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. Serious lapses in judgment and uncritical deference to authority regarding national security issues in the report have clouded his legacy. The Brooklyn Law School Library has in its collection

Chair of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. Serious lapses in judgment and uncritical deference to authority regarding national security issues in the report have clouded his legacy. The Brooklyn Law School Library has in its collection  To commemorate Women’s History Month, Brooklyn Law School Associate Librarian Linda Holmes has added some interesting titles in the display case on the first of the library opposite the elevator, including

To commemorate Women’s History Month, Brooklyn Law School Associate Librarian Linda Holmes has added some interesting titles in the display case on the first of the library opposite the elevator, including