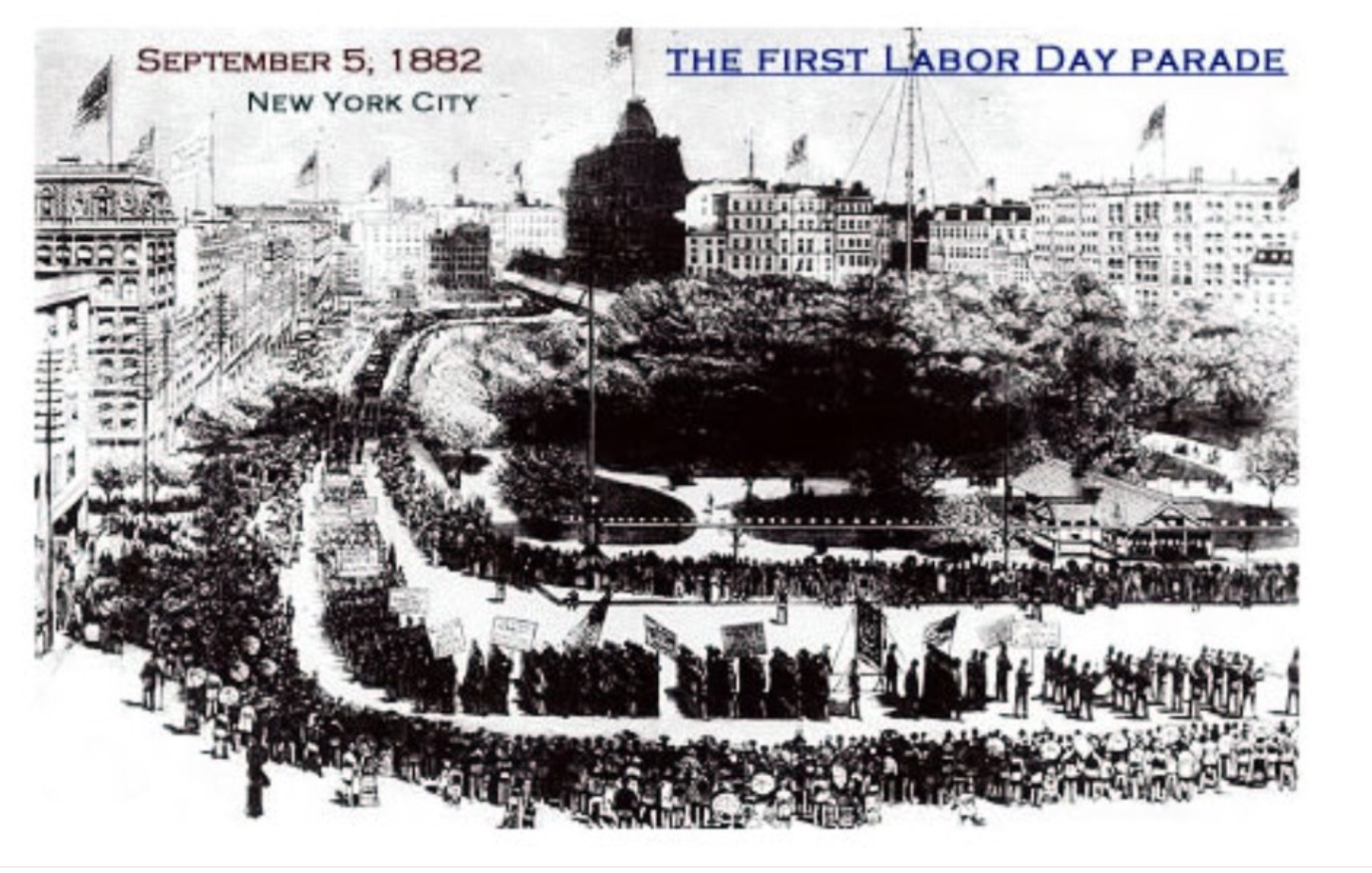

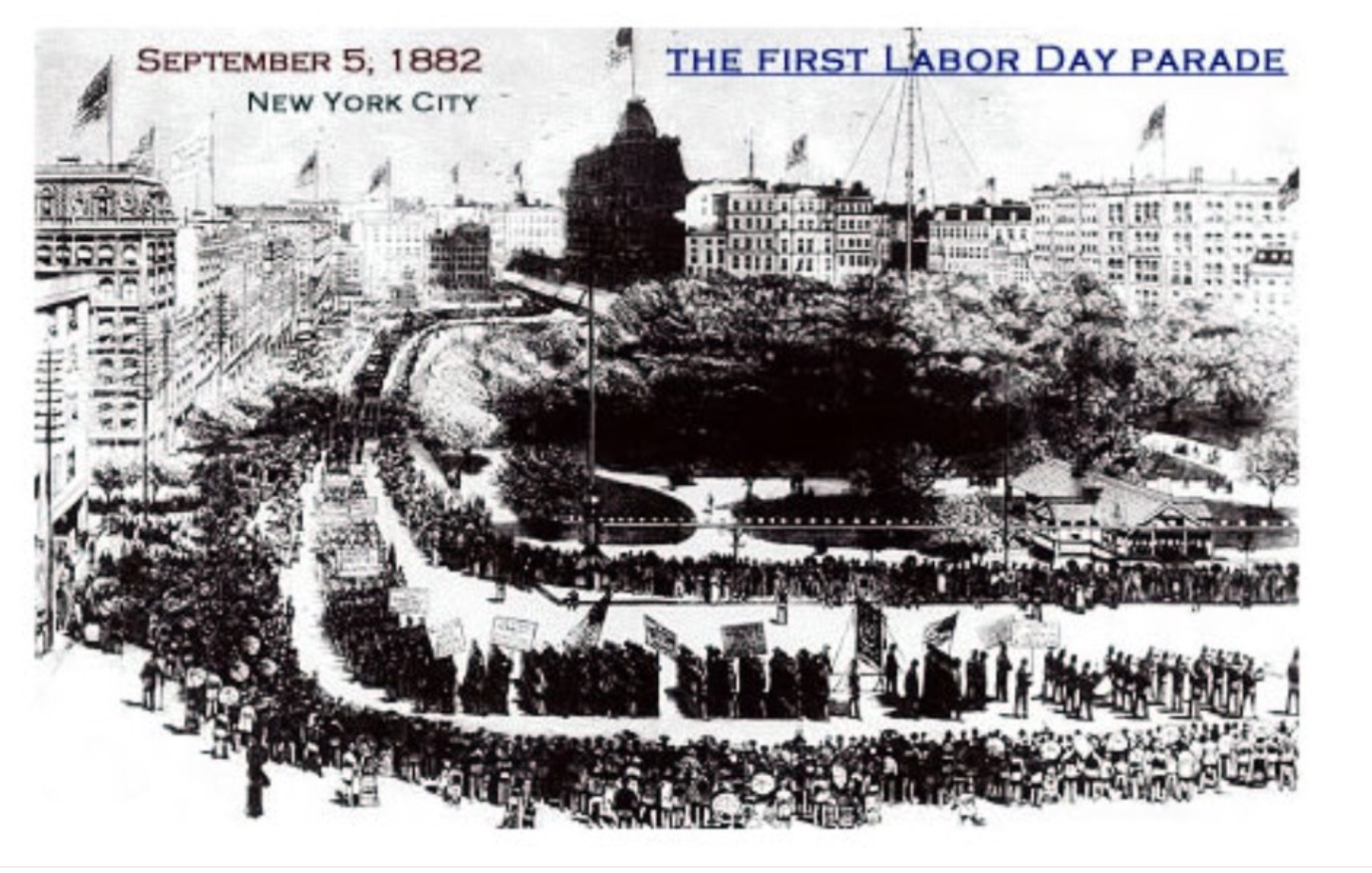

With labor union membership under 12% of the US workforce from a high of 33.2% in 1955, most Americans still appreciate a day off to barbecue, a marked contrast from storming the barricades as occurred during 19th century Labor Days. In the US, Labor Day takes place on the first Monday in September by law. See 5 U.S. Code § 6103. Outside the US, Labor Day falls on May 1. The two separate Labor Days cause some confusion. Labor Day and May Day have in common the celebration of laborers from an era when labor was more grueling than what we think of today. The first Labor Day occurred in NYC’s Union Square on September 5, 1882, when 10,000 union workers marched in a parade honoring American workers, who at the time had none of the labor laws we now take for granted. Labor Day sentiment spread across America when, in 1887 Oregon, followed by a number of other states, adopted Labor Day as a holiday.

With labor union membership under 12% of the US workforce from a high of 33.2% in 1955, most Americans still appreciate a day off to barbecue, a marked contrast from storming the barricades as occurred during 19th century Labor Days. In the US, Labor Day takes place on the first Monday in September by law. See 5 U.S. Code § 6103. Outside the US, Labor Day falls on May 1. The two separate Labor Days cause some confusion. Labor Day and May Day have in common the celebration of laborers from an era when labor was more grueling than what we think of today. The first Labor Day occurred in NYC’s Union Square on September 5, 1882, when 10,000 union workers marched in a parade honoring American workers, who at the time had none of the labor laws we now take for granted. Labor Day sentiment spread across America when, in 1887 Oregon, followed by a number of other states, adopted Labor Day as a holiday.

The adoption of the holiday did not remedy the labor situation in Industrial Revolution-era America. In 1894 the railroad system was nearly halted by a strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company, a company that mistreated its workers. In reaction to the strike, President Grover Cleveland mobilized federal troops which escalated the violence resulting in several deaths. President Cleveland, in an effort to appease an angry public, passed a bill making Labor Day a national holiday. Labor Day continues as a reminder of the struggle of the labor workforce.

Outside the US, laborers are honored on May Day also known as International Workers’ Day. This holiday was instituted worldwide in response to the Haymarket Riot of 1886, a peaceful protest gone awry with another violent altercation against the Chicago workforce by the police. Although the events leading to the creation of May Day took place in America, the US never adopted it as a legal holiday. It was embraced in the Soviet-bloc. With the fall of communism, the holiday is now removed from its violent origins, much like Labor Day in America, now little remembered for the labor required for this holiday.

Consider the debates that animated Chicago’s inaugural Labor Day celebration in 1885:

On Sunday, September 6th, organized labor’s most radical wing led a preemptive march of more than 5,000 persons in an anarchist and socialist-led demonstration, which included representatives from different unions carrying banners with messages such as: “The greatest crime today is poverty!”; “Capital represents stolen labor”; and “Every government is a conspiracy of the rich against the people.” The city’s rank-and-file had decided to boycott the festivities on the grounds that the red flag, radicalism’s most potent symbol, had been expressly banned. The dispute was symptomatic of larger differences within labor’s camp. The anarchist Sam Fielden emphasized these in his remarks, declaring, “There is going to be a parade tomorrow. Those fellows want to reconcile labor and capital. They want to reconcile you to your starving shanties.” The Chicago Daily Tribune decried the radical demonstration in an article entitled “Cutthroats of Society,” which began, “With the smell of gin and beer, with blood-red flags and redder noses, and with banners inscribed with revolutionary mottoes, the anarchists inaugurated their grand parade and picnic.”

Monday, September 7th, saw another parade by the mainstream Trade and Labor Assembly. They, too, carried banners with more moderate tones: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”; “We do not ask for charity, but simple justice”; and “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for recreation.” The Trade and Labor Assembly’s march received more favorable reviews from middle-class voices and was even outright celebrated by some. But respectable opinion could turn as rapidly on the trade unions as it did on the anarchists. Just two months before Labor Day, the police had violently subdued a streetcar workers’ strike. In the process they won the admiration of many middle-class Chicagoans, including one minister who used his pulpit to urge the authorities to maintain order, even if it required them “to mow down the crowds with artillery.”

These glimpses of the tensions in earlier Labor Day celebrations show major differences between the late 19th century Gilded Age and current times. Today, we see disparities between rich and poor nearing historic proportions, yet Americans do not debate the morality of capitalism that consumed those who lived through industrialization’s peak decades. The Gilded Age is a world removed from our own and yet one that on Labor Day is worth revisiting. Users of the Brooklyn Law school Library can get a sense of that period by reviewing the book in the BLS collection New York Labor Heritage: a Selected Bibliography of New York City Labor History by Robert Wechsler, Call No. Z7164.L1 W38.

A BLS Library Blog post titled

A BLS Library Blog post titled  Earlier this year, the NYC Council passed legislation,

Earlier this year, the NYC Council passed legislation,  The Brooklyn Law School Library has in its collection

The Brooklyn Law School Library has in its collection

When the law was enacted, there were already 35 national monuments and parks including Yosemite National Park

When the law was enacted, there were already 35 national monuments and parks including Yosemite National Park  In Constitutional Law courses law students at BLS and throughout the country learn that the decision by Chief Justice John Marshall in

In Constitutional Law courses law students at BLS and throughout the country learn that the decision by Chief Justice John Marshall in